How Escorts Shaped Paris' Art and Literature Scene

Paris in the 19th and early 20th centuries wasn’t just about cafés and canvases-it was alive with women who moved between worlds. They weren’t just companions. They were muses, confidantes, and sometimes the only people who truly saw the artists and writers drowning in their own genius. These women, often called escorts, played a quiet but powerful role in shaping the city’s most enduring art and literature.

The Real Muse Behind the Masterpieces

When you think of Monet’s women, you picture soft light and flowing dresses. But the model for his early works, Camille Doncieux, wasn’t just a pretty face. She was his wife, yes-but before that, she worked as a companion to wealthy patrons. Her presence in his studio wasn’t accidental. She understood the rhythm of his moods, the way he needed silence before he painted, and how to hold still for hours without complaining. She didn’t just pose-she held space for his vision.

Same with Suzanne Valadon. She started as a model for Degas, Renoir, and Toulouse-Lautrec. She didn’t wait to be discovered. She learned to paint by watching them, stealing brushes, copying their sketches. Eventually, she became one of the first women to exhibit at the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. Her work? Raw, honest, unfiltered. She painted women as they were-not idealized, not eroticized. Her subjects were laundresses, dancers, and yes, other women who lived on the edges of society. She knew their lives because she’d lived them.

Writers and Their Quiet Partners

Ernest Hemingway wrote about Paris like it was a lover. But the woman who kept him grounded during those lean years wasn’t his wife Hadley. It was Alice B. Toklas, his partner, yes-but also someone who managed his finances, hosted salons, and introduced him to people who mattered. She wasn’t an escort in the modern sense, but she operated in the same gray zone: paid for companionship, lived in the margins of high society, and had access to the inner circles of writers and artists.

Then there’s Colette. She wrote Chéri and Gigi after years of living with her husband, Willy, who forced her to write under his name. She didn’t just write about escorts-she was one, in a way. She performed, she charmed, she negotiated her worth. When she finally broke free, she didn’t just become a famous author-she became a symbol of female autonomy in a world that tried to silence her.

Many writers in Montparnasse relied on women who could listen without judgment, who didn’t care about their fame, and who didn’t expect anything in return except a roof, a meal, and maybe a little affection. These women kept the conversation going when the alcohol ran out and the inspiration dried up.

The Café Culture Was Built on Their Presence

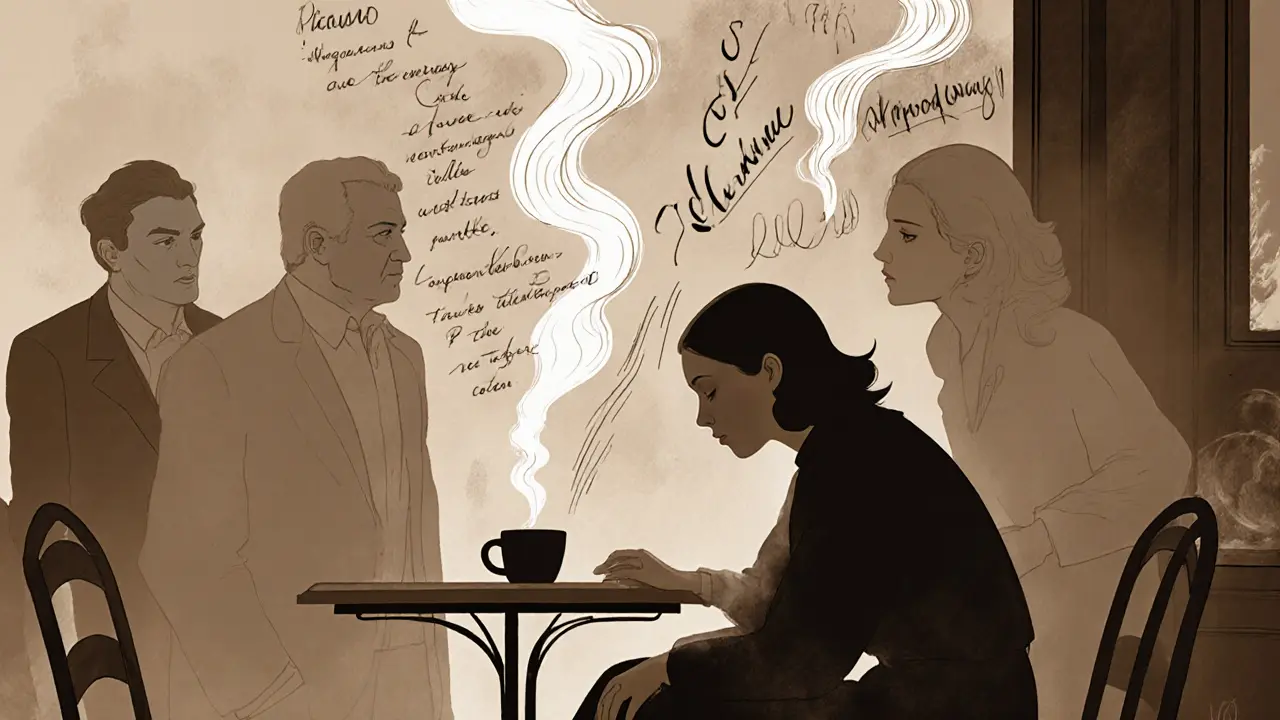

La Coupole, Le Dôme, Les Deux Magots-these weren’t just cafes. They were stages. And the women who sat at the corners of tables, sipping coffee while artists argued about cubism or poets read aloud their latest lines, weren’t background noise. They were the glue.

They brought a sense of normalcy to chaotic lives. A writer who hadn’t eaten in two days could be fed by a woman who’d just finished a long night with a client. A painter who’d just been rejected by the Salon could find comfort in a touch, a quiet word, a shared cigarette. These women didn’t need to be famous to matter. Their value wasn’t in their looks-it was in their presence.

They were the ones who remembered which poet liked his coffee black, which sculptor needed silence after midnight, which writer cried when he talked about his mother. They kept records no one else bothered to keep.

How They Changed the Art

Before these women, female figures in art were angels, saints, or nymphs. Then came the real ones: tired, bold, unapologetic. The women who modeled for Picasso weren’t just bodies-they were personalities. One of his most famous portraits, Portrait of Dora Maar, wasn’t just a painting. It was a document of a relationship. Dora wasn’t just his lover. She was a photographer, a poet, and someone who challenged him. She made him see differently.

And then there’s the literature. In Jean Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers, the protagonist is a thief and a hustler. But the women around him? They’re not side characters. They’re the ones who hold the world together. Genet didn’t romanticize them-he gave them dignity. That was revolutionary.

These women didn’t ask to be immortalized. But their influence was too deep to ignore. Artists didn’t paint them because they were beautiful. They painted them because they were real.

The Myth and the Reality

Today, people talk about Parisian escorts like they’re part of some romantic fantasy-glamorous, dangerous, free. But the truth was messier. Many of these women lived in fear. They were vulnerable to police raids, exploitation, and violence. Some were young. Some were immigrants. Some were mothers. They didn’t choose this life because they wanted to be muses. They chose it because they had no other options.

But here’s the thing: even in hardship, they created. They whispered ideas into ears. They held hands when no one else would. They made space for art to breathe. And in doing so, they changed the course of culture.

Why This Matters Today

When we look at a painting by Modigliani or read a line from Sartre, we don’t always think about the woman who sat across from the artist, listening while he poured out his soul. But she was there. She was part of the process.

Modern art and literature didn’t rise in a vacuum. It rose because someone was willing to sit in silence, to offer warmth, to be seen without being judged. That’s not a side note-it’s the foundation.

Today’s artists still need that. They still need people who listen without an agenda, who don’t care about fame but care about truth. The role of the companion, the listener, the quiet force behind the creation-that hasn’t disappeared. It’s just less visible now.

Paris didn’t become the capital of art because of its museums. It became that because of the women who made the studios, the cafés, the late-night conversations possible. They weren’t just escorts. They were the unseen architects of genius.

Were escorts in Paris just sex workers?

No-not in the way we think of it today. Many women in Paris during the 1800s and early 1900s provided companionship, emotional support, and social access in exchange for money or shelter. Some did have sexual relationships, but many didn’t. Their value was in their presence, their intelligence, their ability to listen, and their connection to artistic circles. They were often more like confidantes, managers, or muses than what modern society labels as sex workers.

Did any famous artists admit their escorts were muses?

Yes. Toulouse-Lautrec openly painted his circle of companions, including Jane Avril and La Goulue, and called them his friends. Picasso kept Dora Maar’s letters and acknowledged her influence on his work. Colette wrote about women like herself in her novels, turning their lives into literature. These artists didn’t hide their relationships-they celebrated them, even when society didn’t.

How did escorts gain access to elite art circles?

Many started as models or café regulars. Artists and writers frequented the same places-Montparnasse, Saint-Germain-des-Prés-and formed relationships over time. Some escorts were well-read, spoke multiple languages, and knew how to navigate social hierarchies. They weren’t just hired for looks-they were hired for their wit, their charm, and their ability to make people feel seen. That’s how they became insiders.

Were these women paid well?

It varied. Some earned enough to live comfortably-especially those who worked with wealthy patrons or became famous models. Others barely scraped by. Many lived in shared apartments, moved frequently, and depended on multiple clients. Pay wasn’t always in cash-sometimes it was food, a place to sleep, or access to a studio. Their survival depended on adaptability, not just beauty.

Is this still happening in Paris today?

The form has changed, but the dynamic hasn’t vanished. Today, some artists still rely on companions who offer emotional and intellectual support. While modern escorts operate under different legal and social frameworks, the role of the quiet, perceptive companion who helps creative people stay grounded remains. The difference now is that these relationships are less visible-and less documented.